Senpai wa Otokonoko – Glossary and Translation Comparisons

Licensed translations of Senpai wa Otokonoko are available in seven languages. This page will be updated as additional translations are released.

| Language | Publisher | Publication Date |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | LINE Manga (serialization; e-book) Ichijinsha (print) | December 7, 2019 – December 30, 2021 November 25, 2021 – present |

| English | WEBTOON | March 9, 2023 – February 8, 2024 |

| Traditional Chinese | LINE WEBTOON (serialization) Tong Li Publishing Co., Ltd. (print) | December 25, 2021 – November 4, 2023 March 6, 2023 – present |

| Simplified Chinese | Dongman Manhua | December 27, 2021 – March 22, 2023 |

| Thai | LINE WEBTOON | February 13, 2022 – December 24, 2023 |

| Korean | NAVER WEBTOON (serialization) Daewon C.I. Inc. (print) | February 18, 2022 – September 2, 2023 July 13, 2023 – present |

| French | WEBTOON | March 28, 2022 – February 5, 2024 |

| German | WEBTOON | May 28, 2022 – hiatus |

(Note: I don’t have access to print copies outside of Japanese, of which the print releases in Korea and Taiwan use a different translation from WEBTOON. Unless otherwise specified, names and scenes were checked against the WEBTOON version.)

Series Info | Glossary

Title

| Language | Title | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 先輩はおとこのこ Senpai wa Otokonoko | [My] Senpai is an Otokonoko/a Boy |

| English | Senpai is an Otokonoko | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 前輩是偽娘 Qiánbèi Shì Wèiniáng (serialization) 學姊是男孩 Xuézǐ Shì Nánhái (print) | [My] Senpai is an Otokonoko [My] Female Senior is a Boy |

| Simplified Chinese | 前辈是男孩子 Qiánbèi Shì Nánháizi | [My] Senpai is a Boy |

| Thai | รุ่นพี่สุดสวยคนนี้เป็นผู้ชาย Runphi Sutsuai Khonni Pen Phuchai | This Gorgeous Senpai is a Man |

| Korean | 선배는 남자아이 Seonbae-neun Namjaai | [My] Senpai is a Boy |

| French | My crossdressing crush | — |

| German | My Crossdressing Crush | — |

The Japanese title writes おとこのこ otokonoko in hiragana phonetically, so it could be interpreted both as 男の子 “boy” or as 男の娘 “otokonoko” (a boy who acts femininely, such as by crossdressing). The Traditional Chinese, French, and German translations go with the “crossdressing” interpretation, while the Simplified Chinese, Thai, and Korean translations go with the “boy” interpretation. Note that the Thai logo has an exclamation mark at the end that is not present in the text title on WEBTOON.

The Traditional Chinese print version translated “senpai” using the feminine word 學姊 xuézǐ instead of the gender-neutral word 前輩 qiánbèi that WEBTOON does. This allows it to draw a direct contrast between Makoto’s feminine appearance at school with him being a boy, without relying on the Japanese-inspired 偽娘 wèiniáng.

The English translation goes with leaving it as “otokonoko”, and puts a translator’s note at the end of the first chapter that “Otokonoko is a Japanese term used for men who have a culturally more feminine gender expression.” It doesn’t mention the “boy” interpretation, however.

The title is presented from Saki’s perspective, with her senpai being Makoto. In Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, pronouns do not have to be included when they can be inferred, so “my” does not have to be included explicitly. In English, French, and German, pronouns must be included for it to be grammatically correct. The French and German translations refer to Makoto as her “crush” instead of as her “senpai”, likely to avoid using the Japanese word directly. Note that the French logo is in title case while it is in sentence case for the text title on WEBTOON.

It’s common for media such as manga and webtoons to use English titles in France and Germany, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the French and German titles are in English, even differing from the official English title. This can be because the licensor specifies what title international releases should use (typically one in English), or because the licensee wants to keep an English title for mass market appeal or stylistic reasons.

Characters

| Language | Makoto Hanaoka | Saki Aoi | Ryuji Taiga |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 花岡まこと Hanaoka Makoto | 蒼井咲 Aoi Saki | 大我竜二 Taiga Ryūji |

| English | Makoto Hanaoka | Saki Aoi | Ryuji Taiga |

| Traditional Chinese | 花岡真琴 / 花岡眞琴 Huāgāng Zhēnqín | 蒼井咲 Cāngjǐng Xiào | 大我龍二 Dàwǒ Lóng’èr |

| Simplified Chinese | 花岗真琴 Huāgāng Zhēnqín | 苍井咲 Cāngjǐng Xiào | 大我龙二 Dàwǒ Lóng’èr |

| Thai | ฮานาโอกะ มาโคโตะ Hanaoka Makhoto | อาโออิ ซากิ Aoi Saki | ไทงะ ริวจิ Thainga Riochi |

| Korean | 하나오카 마코토 Hanaoka Makoto | 아오이 사키 Aoi Saki | 타이가 류지 Taiga Ryuji |

| French | Makoto Hanaoka | Saki Aoi | Ryûji Taiga |

| German | Makoto Hanaoka | Saki Aoi | Ryûji Taiga |

まこと Makoto is a unisex name. It can be more clearly gendered when written in kanji, with names like 誠 being more masculine and names like 真琴 or 麻琴 being more feminine.

Their Chinese names are simply their Japanese names read in Chinese. Note that Makoto’s name also has to be written using Chinese characters, so it’s given the kanji 真琴, which leans feminine in Japanese. The primary dialogue font of the Traditional Chinese translation uses the traditional form 眞 of the character 真 zhēn, but it makes no difference in terms of meaning.

Their Thai and Korean names are fairly straightforward transcriptions of their Japanese names. Taiga is typically transcribed as ไทกะ Thaika in Thai, but since /g/ can be pronounced as a ng sound [ŋ] in the middle of words, this spelling also sees some use.

Their English, French, and German names are romanizations of their Japanese names, presented in Western order (given name then family name). The circumflex (^) in Ryuji’s name in French and German indicates a long vowel, much like the macron (¯) does in Hepburn. For French and German speakers, vowels with a circumflex are typically much easier to type and more likely to be included in fonts than vowels with a macron. On the other hand, English speakers tend to avoid diacritics altogether.

Honorifics

| Language | “Aoi-san” | Meaning | “Senpai” | Meaning | “Shisho” | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 蒼井さん Aoi-san | Ms. Aoi | 先輩 Senpai | Senior, Upperclassman | 師匠 Shisho | Master, Instructor |

| English | Aoi-san | — | Senpai | Senior, Upperclassman | Master | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 蒼井同學 Cāngjǐng tóngxué | Classmate Aoi | 前輩 Qiánbèi | Senior, Senpai | 師父 Shīfu | Master, Teacher |

| Simplified Chinese | 苍井同学 Cāngjǐng tóngxué | Classmate Aoi | 前辈 Qiánbèi | Senior, Senpai | 师父 Shīfu | Master, Teacher |

| Thai | คุณอาโออิ Khun Aoi | Ms. Aoi | รุ่นพี่ Runphi | Senior | อาจารย์ Achan | Teacher, Instructor |

| Korean | 아오이 Aoi | Aoi | 선배 Seonbae | Senior, Upperclassman | 사부님 Sabunim | Master, Instructor |

| French | Aoi | Aoi | Makoto | Makoto | Taiga | Taiga |

| German | Aoi | Aoi | Makoto | Makoto | Taiga | Taiga |

Note that in Japanese, Makoto refers to Ryuji as りゅーじ in hiragana rather than in kanji, but this distinction isn’t retained in any of the translations.

The English translation includes translator’s notes in the first chapter explaining that “Senpai is a term used to address a person who is older, more experienced, or is in a higher social position.” and that “-san is a suffix used to address friends, equals, strangers, and acquaintances.”

The French and German translations drop the honorifics most of the time, and have Saki refer to Ryuji by his surname instead of as Shisho. In the line in Ch. 5 where it’s introduced, Saki calls Ryuji a “genius” instead.

Chapter titles

Only the English and Korean releases translated the chapter titles. While WEBTOON is technologically capable of displaying chapter titles, the other language releases don’t include them and refer to the chapters by their chapter number only. Most of the time the title is just a phrase plucked from the body of the chapter itself, but there are a few exceptions where the title adds something extra that does make this unfortunate.

I don’t have any copies of the Traditional Chinese translation in print, but since the Japanese volumes included the chapter titles and a table of contents, I have no reason to assume they weren’t included.

Note on typesetting

In the original Japanese version as well as the English, Traditional Chinese, Simplified Chinese, Thai, and Korean translations, standard dialogue is in the color black. The panel outlines and the hand-drawn line art, bubble outlines, SFX, and asides are all in the same shade of brown (#41262E).

In the English translation, the font used for thoughts and narration has an awfully wide letter spacing and leading. While it definitely looks distinct from the dialogue font because of this, it’s still a bit off-putting at first.

In the French and German translations, dialogue is also typeset in that particular shade of brown. While they both use WildWords for it, the German translation also chooses to use the same font for asides and the similar-looking Kiss and Tell for SFX. This makes all of the text seem very uniform to me.

Censorship

Belly button (Ch. 1)

You can see from the first few bubbles how the original Japanese version has long bubbles that flow from right-to-left. This is because languages like Japanese and Chinese can be written vertically in columns from right-to-left, so manga likewise adopted that format. Most of the translations keep the Japanese format, except for the Korean and English ones, which redo the bubbles to be wider and rounder to better fit horizontal text in rows, as well as redoing the panel layouts to flow from left to right.

The English version does not include the scene where Makoto is taking off his wig and lifting up his shirt, apparently to comply with local laws and regulations. The version released in Mainland China and South Korea move one of the bubbles to cover up more of Makoto’s midriff, but don’t go so far as to remove the scene entirely. The Traditional Chinese, Thai, French, and German translations keep the scene intact with the original Japanese bubble placement.

Midriff (Ch. 64)

In the flashback in Ch. 64, Makoto is shown presenting as a girl at his high school during his first year. A guy confesses to Makoto, saying that he wants to go out with Makoto. Makoto rejects him, but the guy refuses to give up and grabs Makoto, forcing Makoto to reveal that he’s actually a boy. The guy pushes him to the ground and lifts up his shirt to confirm that he’s a boy.

In the English version, the bottom of the panel where the guy lifts up Makoto’s shirt is cropped out. This keeps his midriff from being shown, likely to comply with local laws and regulations. The Traditional Chinese, Simplified Chinese, Thai, and French translations keep the scene intact.

Toilet (Ch. 70)

In the flashback in Ch. 70, Makoto’s mom is shown during her teenage years. Over the course of the chapter, she discovers that her father is secretly crossdressing. At the end of the chapter, she is shown thinking “Gross.” while vomiting in a toilet.

In the English version, this last panel and thought are blanked out, likely to comply with local laws and regulations. The Traditional Chinese, Simplified Chinese, Thai, and French translations keep the scene intact.

The title of the chapter is also changed. In Japanese and Korean, the chapter is titled 気持ち悪い Kimochi Warui and 역겨워 Yeokgyeowo, which can be translated as “Gross.” The English version changes the title to “Nail Polish,” which is less insulting.

Specific chapters

“Otokonoko” (Ch. 2)

| Language | Word | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 男の娘 Otokonoko | Otokonoko |

| English | Crossdresser | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 偽娘 Wèiniáng | Otokonoko |

| Simplified Chinese | 伪娘 Wěiniáng | Otokonoko |

| Thai | สาวดุ้น Saodun | Otokonoko |

| Korean | 오토코노코 Otokonoko | Otokonoko |

| French | Queer | Queer |

| German | Transgender | Transgender |

The word 男の娘 otokonoko is used in Ch. 2 by Saki, the only time that specific phrase is used in the entire series. Later comments on Makoto’s crossdressing generally use the word 女装 josō “dressing in female clothing, crossdressing (for a male)” instead. The English translation simply uses “crossdresser”.

The Chinese translations use the word 偽娘 / 伪娘 wěiniáng, which was specifically coined to refer to the Japanese concept of otokonoko. The Thai word สาวดุ้น saodun can refer to both futanari and otokonoko. The Korean translation writes “otokonoko” phonetically, and includes a translator’s note in the bottom-right, giving a definition of what it means.

The French translation translates otokonoko as “queer“, set in italics most likely to indicate that it’s an English loanword. The German translation translates it as “transgender“. Let’s take a closer look at her entire set of lines:

| Language | Text | Basic Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | …ひどいです もっとはやく知りたかった まさか 先輩が 男の娘!! (ONAKA..) 最っっっ高じゃないですか!! つまり男バージョンの先輩と女バージョンの先輩をたのしめるってことですか!?!? | …How cruel. I wish I’d known sooner. To think… …that you were… …an otokonoko!! (Your belly…) Isn’t that just the beeest!! Does that mean I can enjoy the guy version of you and the girl version of you?!?! |

| English | …How could you hide something like this? If only I knew sooner. I can’t believe it… You’re… …a crossdresser!! (Your stomach… I can’t even…!) How frigging awesome is that?! So what you’re saying is, I get to enjoy a male and female version of you?! | — |

| French | C’est pas vrai… Si seulement je l’avais su plus tôt… Alors… du coup… t’es un queer ! (Je pensais que t’étais… / une fille !) Mais c’est trop biiien ! Ça veut dire que j’ai le droit à deux version de toi pour le prix d’une ?! | That can’t be true… If only I’d known sooner… So… then… you’re a queer! (I thought you were… / a girl!) But that’s sooo cool! Does that mean I get two versions of you for the price of one?! |

| German | Das ist nicht wahr … Hätte ich das nur früher gewusst … Also … … dann … … du bist transgender?! (Ich dachte, du wärst … / … ein Mädchen!) Das ist ja echt toll! Bedeutet das, dass ich zwei Versionen von dir zum Preis von einer bekomme?! | That can’t be true… If only I’d known sooner… So… …then… …you’re transgender?! (I thought you were… / …a girl!) That’s so cool! Does that mean I get two versions of you for the price of one?! |

I find it interesting how similar the French and German translations are to each other, especially with the translation choices they made compared to the Japanese. Things like the rewrite of the “ONAKA…” aside and the play on the idiom “two for the price of one” make me think that they were both based on the same translation. According to the French translator’s LinkedIn, she translated it from Japanese to French, so it’s most likely that the German translation was via French, especially given how dissimilar they both are from the English.

I’m not sure why they didn’t just refer to Makoto as a “crossdresser” or the like given that that’s what’s in the title, much like how “otokonoko” is in Japanese. Ultimately, I don’t think this scene is too important, since it’s just Saki’s first impression of Makoto after finding out that he crossdresses. Nothing later on references this scene, and whether she assumed correctly or not doesn’t matter.

“Memory of a goldfish” (Ch. 5)

(Coming soon!)

“Telekinesis” (Ch. 6)

Saki and Ryuji communicate with each other non-verbally in Ch. 6

| Language | Text | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 今だったら話しかけていいんですよね?って顔 いーんじゃねぇか?って顔 | A look that says “Now it’d be okay for me to talk to him, right?” A look that says “It’s fine, I guess” |

| English | *Telekinesis* “Now’s okay to talk, tight?” *Telekinesis* “Sure, I guess…” | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 「我現在可以跟他説話了吧?」的表情 「現在應該可以吧」的表情 | A look of “I can talk to him now, right?” A look of “It should be okay now” |

| Simplified Chinese | 现在我可以搭话了吧?的表情 有什么不可以的?的表情 | A look of “Now I can talk to him, right?” A look of “Why not?” |

| Thai | ทําหน้าแบบถ้าเป็นตอนนี้จะชวนคุยก็ได้ใช่มั้ย? ทําหน้าแบบก็น่าจะได้ล่ะมั้ง? | Making a face like “Now it’s okay for me to talk to him, right?” Making a face like “Well, I guess it should be fine?” |

| French | Comprendre : “Du coup, là, c’est bon, je peux lui parler ? Comprendre : “À ton avis ?” | Understand: “So, is it okay now? Can I talk to him?” Understand: “What do you think?” |

| German | Telepathie: „Ist jetzt der richtige Zeitpunkt, um mit ihm zu reden?“ Telepathie: „Wenn du meinst …“ | Telepathy: “Is now the right time to talk to him?” Telepathy: “If you think so…” |

The original Japanese and the Asian translations indicate that Saki and Ryuji are reading each other’s facial expressions to communicate without speaking. The French version translates って顔 it as comprendre, which means “to understand”.

The German version translates it as Telepathie, which means “telepathy”. The English version similarly translates it as “telekinesis.” Note that “telepathy” specifically refers to mind reading, while “telekinesis” refers to a psychic ability to move objects with their mind, such as spoon bending. There’s no telekinesis occurring in this scene, so it’s likely the translator mixed the words up.

“Okama” (Ch. 6)

Ryuji insulting Makoto back when they were in kindergarten in Ch. 6

| Language | Text | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | おい おかまやろう おかまのくせに | Hey, okama. He’s an okama though. |

| English | Hey, Hanaoka. He’s a sissy boy, isn’t he? | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 喂,人妖。 明明是個人妖。 | Hey, tranny. He’s obviously a tranny. |

| Simplified Chinese | 喂,娘娘腔。 明明是個娘娘腔。 | Hey, sissy. He’s obviously a sissy. |

| Thai | เฮ้ย! เจ้ากะเทย เป็นกะเทยแท้ ๆ | Hey! Kathoey. He’s a real kathoey. |

| French | Hé, toi ! La fille manquée ! Il est habillé en fille, pourtant ! | Hey, you! The tomgirl (lit. failed girl)! He’s dressed like a girl, though! |

| German | He, du! Das verlorene Mädchen! Er ist doch wie ein Mädchen angezogen! | Hey, you! The lost girl! He’s dressed like a girl, though! |

In one of the extra chapters included with the first volume, it’s revealed that Ryuji came up with the okama insult based on Makoto’s full name, 花岡まこと Hanaoka Makoto. This pun wouldn’t translate well in any other language without having to change the character’s names.

“Boku”/”Watashi” (Ch. 6/Ch. 14)

Makoto mostly uses the feminine-leaning personal pronoun 私 watashi while dressing as a girl and the masculine-leaning 僕 boku while dressing as a boy, in his thoughts, and when alone with Ryuji from the start of the series until Chapter 14, after which he no longer uses watashi and uses boku even when dressing as a girl. (Ryuji uses 俺 ore and Saki uses 私 watashi.)

| Language | Text | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | おやすみ 私 さよなら 私 | Good night, me (watashi). Goodbye, me (watashi). |

| English | Good night, me. Goodbye, me. | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 晚安,我自己。 永別了,我自己。 | Good night, myself. Farewell, myself. |

| Simplified Chinese | 真琴,晚安。 真琴,永别了。 | Makoto, good night. Makoto, farewell. |

| Thai | ราตรีสวัสดิ์นะตัวฉัน ลาก่อนฉัน | Good night, me. Goodbye, me. |

| French | Bonne nuit, mon autre moi. Adieu, mon autre moi. | Good night, my other self. Goodbye, my other self. |

| German | Gute Nacht, mein anderes Ich. Leb wohl, mein anderes Ich. | Good night, my other self. Goodbye, my other self. |

Chinese and Korean don’t have gendered first-person pronouns. Thai does have gendered first-person pronouns, but it looks like Makoto uses ฉัน chan for both boku and watashi. It appears that it’s more commonly used by women, but some men use it too. The Chinese and Thai translations don’t keep the distinction and have Makoto simply refer to “watashi” as himself. However, this translation choice adds the implication that Makoto is hiding and discarding himself as a whole.

French and German also don’t have gendered first-person pronouns. The French and German translations translate it as “my other self” in the final lines of Ch. 6 and Ch. 14. I think this translation is nice with how it keeps a distinction between the two selves, but it also marks the “other self” as being secondary or less important. For an example of what I mean, would you rather be introduced by someone as their “friend” or as their “other friend”?

Ultimately, which of the two treatments is better comes down to personal preference.

“Renraku” (Ch. 7)

| Language | Text | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 何時間に1回なら連絡していいですか? | How many hours between each time I contact you would be good? |

| English | How often is it okay to mail you? | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 請問我每個小時可以聯絡你一次嗎? | Can I contact you once per hour? |

| Simplified Chinese | 我能多久找你聊一次天啊? | How often can I chat with you? |

| Thai | ให้โทรไปหาทุกกี่ชั่วโมงถึงจะดีเหรอคะ? | How many hours between each call would be good? |

| French | Je pourrai t’appeler combien de fois par jour ?! | How many times a day can I call you?! |

| German | Wie oft am Tag darf ich dich anrufen?! | How many times a day can I call you?! |

This line sets up a joke because of the gap between Saki and Makoto’s expectations: she wants to contact him every few hours, but he only wants her to contact him every three days. The Traditional Chinese and Thai translations keep the joke by keeping the gap between Saki’s expectation of “hours” and Makoto’s reaction of “days”. The French and German translations instead contrast “how many times a day” with “every three days”. The English and Simplified Chinese translations change it so that Saki only asks “how often,” to which “three days” is a reasonable answer.

In Japan, SMS text messaging never caught on because the different cell phone carriers could not agree on a common standard, so you could only text people with the same carrier as you. Instead, Japanese people tended to exchange carrier-provided email addresses to email each other in circumstances where in other countries you would exchange phone numbers to text each other. As messaging apps like LINE increased in popularity, they were also informally included under the “email” umbrella. This leads to some ambiguity, where it can be unclear exactly how people are communicating with each other. In this series, the protagonists explicitly use LINE for their group chats as shown at the start of Ch. 10 in the original Japanese, Traditional Chinese, Thai, French, and German translations.

Missing panels (Ch. 8)

(Coming soon!)

“Uragoe” (Ch. 9)

(Coming soon!)

“Hatsu” (Ch. 11)

| Language | Text | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 初プリ | First purikura |

| English | Netapuri | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 拍貼初體驗 | First photo-taking experience |

| Simplified Chinese | 初次拍摄 | First photo shoot |

| Thai | สวยด้วยแอพ | Pretty with app |

| French | Mon premier purikura | My first purikura |

| German | Mein erstes Purikura | My first purikura |

The English version misread the kanji 初 hatsu as ネタ neta, so they translated it as though it read ネタプリ netapuri.

“Suki na seibetsu” (Ch. 12)

(Coming soon!)

“Dansō” (Ch. 17)

| Language | Text | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 男装してた時は目が死んでたもんな! 男装って何!? | When you were crossdressing as a guy, you eyes were dead! What do you mean by crossdressing as a guy?! |

| English | You were like a zombie, walking around dressed like a guy. What do you mean, “dressed like a guy?!” | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 你扮成男人時, 眼神死氣沉沉的。 什麽叫做扮成男人!? | When you were pretending to be a guy, your eyes were dead. What do you mean by pretending to be a guy?! |

| Simplified Chinese | 你扮男装的时候, 眼睛里都没有神了! 什么叫扮男装啊?! | When you were crossdressing as a guy, your eyes were completely dull! What do you mean by crossdressing as a guy?! |

| Thai | ตอนแต่งชายทําหน้าหมดอาลัยตายอยากน่าดเลยนีนะ! ทีว่าแต่งชายหมายความว่าไง!? | When you were crossdressing as a guy, you looked like you wanted to die! What do you mean by crossdressing as a guy?! |

| French | Parce que t’avais l’air au fond du trou, sapé en mec ! Comment ça, “sapé en mec” ? | Because you looked like you were in the dumps when you dressed like a guy! What do you mean, “dressed like a guy”? |

| German | Du sahst nämlich aus, als wärst du in ein tiefes Loch gefallen, als du dich wie ein Kerl angezogen hast! Wie meinst du das, „wie ein Kerl angezogen“? | Because you looked like you fell into a deep hole when you dressed like a guy! What do you mean, “dressed like a guy”? |

The phrases 女装 josō and 男装 dansō literally mean “women’s clothing” and “men’s clothing”, but in Japanese, they specifically refer to when someone crossdresses and wears these clothes. From this, we get phrases like 女装男子 josō danshi, which means “crossdressing boy (boy wearing female clothing)”, and 男装女子 dansō joshi, which means “crossdressing girl (girl wearing male clothing)”.

In the original, the joke is that Ryuji’s word choice insinuates that Makoto was basically a girl crossdressing as a guy. In the English translation, they translated 男装 dansō as “dressed like a guy”. The implication here is less clear-cut, since a guy can “dress like a guy” in English, so the implication that the subject must be a girl is not as present.

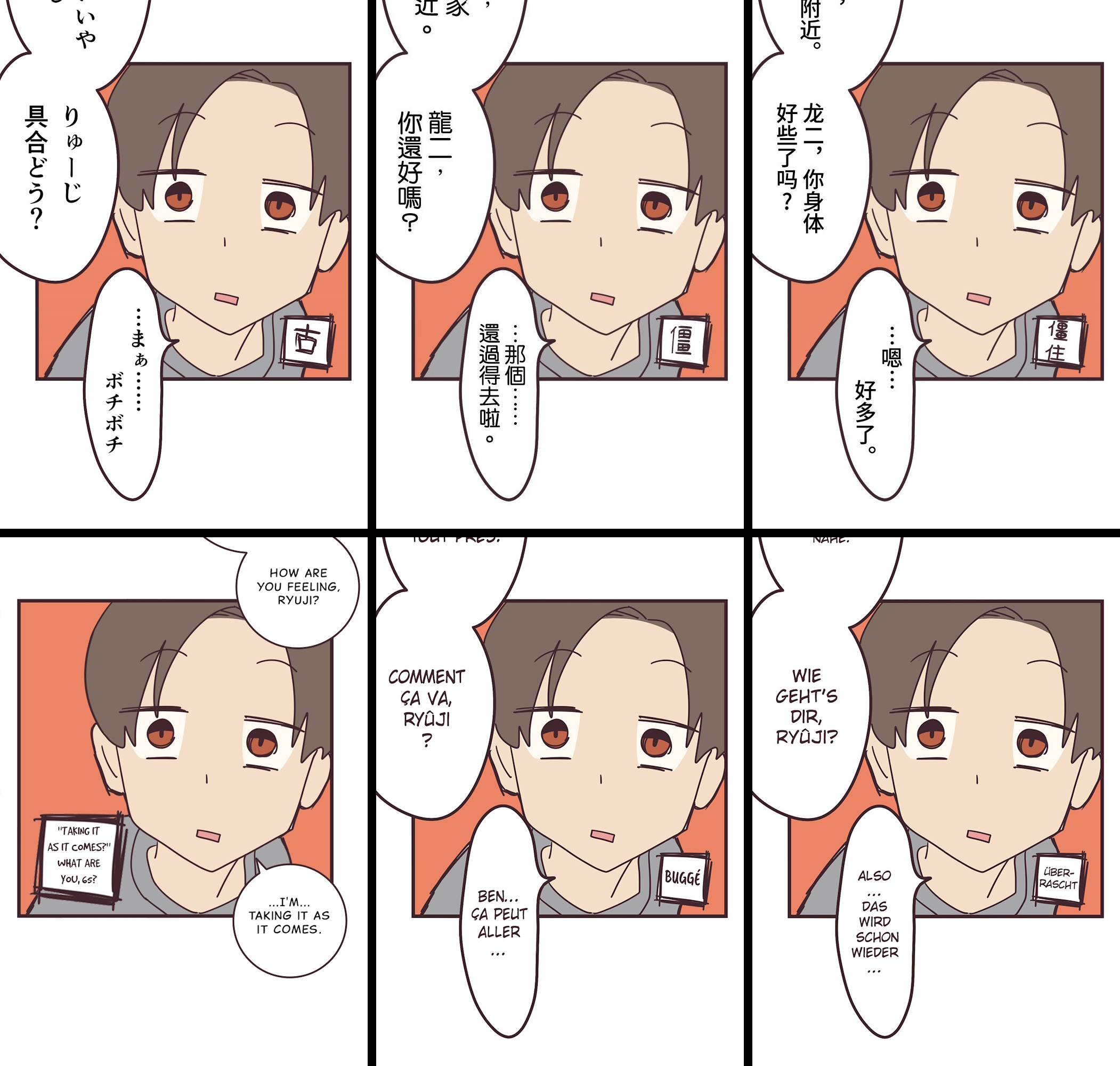

“Old” vs. “stiff” (Ch. 29)

| Language | Text | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 固 | Stiff |

| English | “Taking it as it comes?” What are you, 65? | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 僵 | Stiff |

| Simplified Chinese | 僵住 | Frozen |

| Thai | แข็ง | Stiff |

| French | Buggé | Bugged |

| German | Überrascht | Surprised |

The English version misinterprets 固 “stiff” as 古 “old” in a box. This led them to rewrite the line as a comment on Ryuji’s choice of words.

Tally marks and hanamaru (Ch. 33)

| Language | Text | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Japanese | 文化祭 ・💮おばけ屋敷 正正正正㇐ ・カフェ 正正丅 ・屋台 正下 | Cultural Festival ・💮Haunted House 21 votes ・Café 12 votes ・[Food] Stall 8 votes |

| English | School festival •Haunted house 💮 (in progress) •cafe (in progress) •chat stall (in progress) | — |

| Traditional Chinese | 文化祭 ・💮鬼屋 正正正正㇐ ・咖啡 正正丅 ・攤販 正下 | Cultural Festival ・💮Haunted House 21 votes ・Café 12 votes ・Food Stall 8 votes |

| Simplified Chinese | 文化节 ・💮鬼屋 正正正正㇐ ・咖啡馆 正正丅 ・美食摊 正下 | Cultural Festival ・💮Haunted House 21 votes ・Café 12 votes ・Food Stall 8 votes |

| Thai | งานวัฒนธรรม ・💮บ้านผีสิง ・ร้านกาแฟ ・แผงลอย | Cultural Festival ・💮Haunted House 20 votes ・Coffee Shop 11 votes ・Stall 7 votes |

| French | Fête du lycée 💮 • Maison hantée • Salon de thé • Snack | School festival 💮 • Haunted house: 21 votes • Tearoom: 12 votes • Snack bar: 9 votes |

| German | Schulfest 💮 • Geisterhaus • Café • Schnellimbiss | School festival 💮 • Haunted house: 21 votes • Café: 12 votes • Snack bar: 9 votes |

Chapter 33 starts with a shot of a blackboard in Saki’s classroom, establishing that her class is preparing for the school festival. What you’re supposed to take away from the details on the blackboard is that: one, Saki’s class voted on what to do for the school festival; and two, the haunted house won.

To show this, the blackboard shows tally marks to indicate how many votes each option received. The original Japanese version and the Chinese translations use the five strokes of the character 正 as a tally mark; the French and German translations use the five lines of ![]() as a tally mark; and the Thai translation uses the five lines of

as a tally mark; and the Thai translation uses the five lines of ![]() as a tally mark. The English translation instead writes that the three projects are all “in progress”, which is incorrect.

as a tally mark. The English translation instead writes that the three projects are all “in progress”, which is incorrect.

The flower drawn in red chalk is a hanamaru, a variant of the circle mark which is used to reward students for good work at school, similarly to a gold star. In this case, it’s being used to mark the winner of the vote.

“Busybody” (Ch. 42)

In Japanese and Korean, this chapter is titled 不審者 Fushinsha and 수상한 사람 Susanghan Saram, which can be literally translated as “someone suspicious.” This is in reference to the suspicious person that caused club activities to be canceled and the person Saki suspected was near her home in the previous chapter.

In English, this chapter is titled “Busybody,” defined as “someone who meddles in the affairs of others.” Neither Ryuji nor Saki fit this description, and neither does the suspicious person or the person who enters her house at the end of the chapter. What I’m guessing might have happened is that the title was originally translated as “intruder” in the “trespasser” sense, but was changed to “busybody” since it can mean “intruder” in the “meddler” sense.

Content warning (Ch. 64)

The English version of Ch. 64 includes the following warning:

Warning

This episode contains depictions of sexual assault and other disturbing imagery that may be upsetting for some readers.

This warning is not included in any other language.

Flashback (Ch. 64)

During the flashback in Ch. 64 before Makoto’s sex is revealed to the other characters, the English version rewrites the dialogue to be gender-neutral for Makoto, including a line that calls him a “pretty girl.” This is an odd choice, especially given that all of these characters assume that Makoto is a girl at this point. Hayase’s narration also uses masculine pronouns for Makoto.

In other languages such as Chinese, feminine pronouns are used for Makoto in both the flashback and the narration at this point. The French version also uses feminine pronouns in the flashback.

Credits (Ch. 88-100)

In the French translation, only the last 13 chapters have staff credits at the end. Specifically, they credit Claire Olivier as the translator, Anaïs Koechlin as the proofreader, and Catherine Bouvier as the letterer (all from Blackstudio). Since the previous 87 chapters lack these credits, it’s probable that they were worked on by someone else.

That’s all for now, but if you have any suggestions for other scenes I should take a look at, let me know on the Discord. I’ll be updating this page as more chapters and translations come out.